The shocking thing about shock is that most of us have a fairly muddled understanding of it. When we think of shock what often comes to mind is a sudden anxiety producing surprise – something that generates a reaction to fight, flight, or faint. It might be the way you feel after:

- a near miss traffic accident

- seeing a loved one bleeding at an alarming rate

- realizing your required final examination was yesterday, not today

Types of Shock

Psychological Shock

This type of shock may be psychological (of the mind) rather than physiological (of the body). Because of this, it can also be seen by others as a weakness. Not everyone goes into shock at the sight of blood. Experiencing this type of shock may suggest your mind is just not tough enough to take it. Chuck Norris would never experience psychological shock.

Stress and anxiety can produce very real shock-like symptoms such as elevated heart rate, rapid respiratory rate, and pale clammy skin. The treatment for this shock is to calm the patient. For example you may:

- have them lie down

- cover them with a blanket

- gently elevate their feet

- if appropriate, provide fluids

The cynical view is that you simply need to baby this baby. Viewing shock as a mere mental weakness is dangerous, however, because there are in fact physiological causes of shock with very similar symptoms, which are indeed life threatening.

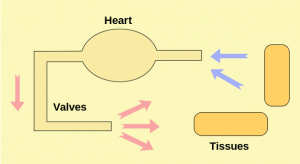

Circulatory Shock

Circulatory shock, also sometimes referred to as medical shock, is caused by a lack of perfusion. The root for perfusion is French and it means to “pour over.” Perfusion simply means pushing blood under pressure to bathe our cells in oxygen. In the wilderness a lack of bathing is usually a bad thing, but a lack of oxygen bathing the cells is a very bad thing. This is not simply a weak state of mind, but a real threat to life.

Proper perfusion relies on a successful cardiovascular systems. We need to keep oxygenated blood pumping through our body. The proper medical terms may be confusing, but the the basic concepts are fairly clear:

- Is there enough volume of blood in the body?

- Is the pump (heart) working properly?

- Are the pipes (vascular system) clear and properly sized?

Hypovolemic Shock

Hypovolemic shock means you do not have enough volume of blood for successful cell bathing. This may be caused by things such as bleeding, dehydration, vomiting, diarrhea, and sever burns. Quickly addressing the cause of the lack of blood volume is critical for treatment.

Cardiogenic Shock

Cardiogenic shock means the heart is not adequately pumping blood through the system. This could be caused by a heart attack or a heart trauma. Treating this root cause in the field may not be practical, so evacuation is key.

Distributive (or Vaseogenic) Shock

Distributive shock means the blood is not being distributed properly through the vascular system. Proper blood pressure is key to distribution, and under normal operation your pipes can constrict or expand to adjust to the right pressure. There are a variety of situations which can disrupt this system, such as nerve damage (neurogenic), infection (septic) or allergic reaction (anaphylatic). Where possible, treating the cause is critical. For example infections may need antibiotics and anaphylaxis may require antihistamines and epinephrine.

The Shocking Reality

Regardless of the cause of shock (failure of volume, pump, or pipes) left untreated patients will slide down a predictable slippery slope. Early treatment is critical to prevent this progression towards death. The progression has three major states:

- Compensatory Shock

- Progressive (or Decompensatory) Shock

- Refractory (or Irreversible) Shock

Compensatory Shock

Compensatory shock means there is something seriously wrong, but your body is managing to keep your blood pressure relatively normal by doing some pretty crazy things. In other words, it is frantically “compensating.” This compensation comes in the form of higher respiratory rates, higher heart rate, tighter vascular constriction – anything to keep oxygenated blood bathing those cells.

Progressive (or Decompensatory) Shock

In progressive or decompensatory shock, your body is beginning to lose the battle. Your compensation efforts to keep blood pressure normal are failing. Less oxygen is getting to the cells, including your brain, and aggressive treatment to turn things around is critical before it is too late.

Refractory (or Irreversible) Shock

Bummer. The title pretty much gives this one away. At some point the lack of oxygen causes your organs to die, including your brain. Some refer to this stage as the “slow circling of the drain.” It is irreversible and death is inevitable. On a brighter note, you won’t be alone in this journey, because by definition everyone will eventually get here. It is essentially how we die.

General Shock Treatment

Shock treatment should not to be confused with shock therapy, which you may want after reading that last depressing paragraph. There are things that can be done to treat circulatory shock (or at least delay if for a significant number of years). Much of the treatment for physiological shock is the same as for psychological, with one significant addition:

- treat the cause

- have them lie down

- cover them with a blanket

- gently elevate their feet

- if appropriate, provide fluids

Patients who do not show vital sign improvements should be evacuated.

Conclusion

There are a wide variety of causes of circulatory shock, but they can all progress down a slippery slope towards death. To be on the safe side, anytime someone appears in distress, you should probably assume shock and treat for it until proven otherwise. Besides, who doesn’t enjoy a calming voice, a warm blanket, and chance to lie down with their feet up.

Disclaimer: I am not a doctor, and do not pretend to be. For more information, ask your doctor, and check medical online references, such as www.webmd.com.