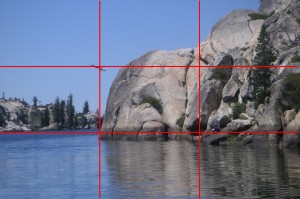

During my Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) thru-hike, I took a very popular side trip to the top of Fisherman’s Peak. Perhaps not surprising, this peak was named in honor of the three fishermen, who on August 18, 1873, were the first ever to reach its summit. Surprising to me, however, is the limited respect accorded these high climbing anglers: Charles Begole, A. H. Johnson, and John Lucas. After all, at 14,494 ft, Fisherman’s Peak is the highest mountain in the contiguous United States.

“Wait,” I hear you saying. “I thought Mount Whitney was the highest peak.” Well, yes, I suppose the mountain is also known by that name. This mountain naming business can be kind of tricky.

According to the Geonames website:

The U.S. Board on Geographic Names is a Federal body created in 1890 and established in its present form by Public Law in 1947 to maintain uniform geographic name usage throughout the Federal Government.

Because serious naming conflicts needed to be resolved,

President Benjamin Harrison signed an Executive Order establishing the Board and giving it authority to resolve unsettled geographic names questions.

Perhaps because of his commitment to resolving identity crises, Benjamin Harrison is now the official name for two elementary schools, a post office, a state park and natural preserve, a mine, and a memorial bridge – at least according to theGeographic Names Information System (GNIS) database.

So why do most people associate the highest continental peak with Whitney rather than the first-to-summit fishermen? It may be as simple as who you know.

Professor Josiah Dwight Whitney of Harvard was tasked with the 1860 California State Geological Survey. He hired a variety of scientist and explorers to help, including William H Brewer, Charles F Hoffmann, William More Gabb and Clarence King. You may also know them as: Mount Brewer, Mount Hoffmann, Mount Gabb, and just to mix things up – Clarence King Mountain. It must have been exhausting hiking around naming mountains after each other.

It was Clarence King who, in an apparent 1864 career enhancing move, suggested his boss Whitney for the highest peak. To explain King’s relationship with the summit, you could sum it up as: D’oh!

In 1864 King attempted to reach the summit and failed.

In 1871 he returned and climbed the wrong summit, peaking out on present day Mount Langley. He wrote extensively about his first-to-ascend Whitney adventure, only later in 1873 to have rival Goodyear let all the air out of his tired tale.

In 1873, King rushed back to climb the correct peak, to claim his place in the history books. With apologies to Gale Sayers, this new book could be titled I Am Third, as he appears to have been beaten out by both the fishermen and the team of Hunter and Crapo.

King sheepishly added the following to the Mount Whitney chapter of his book Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada:

The preceding pages were written immediately after my return from Mount Whitney, and without a shadow of suspicion that among the sea of peaks half seen, half storm-hidden, I could have missed the true summit.

In addition to the peak, I think he missed the point. King’s problem was that he returned from Mount Langley instead of Mount Whitney.

Given his failure as King of the hill, you might assume he gave ground on claiming the naming rights. Perhaps those rights belonged to the fishermen, who simply climbed the correct mountain the first time, probably encumbered with extra poles and a bucket of worms.

Because of King’s less than perfect navigation skills, the lower peak, now known as Mount Langley, was at that time identified as Mount Whitney.

In Exploration of the Sierra Nevada, Francis P. Farquhar (aka Mount Farquhar) recalls a letter written by Goodyear to the Inyo Independent on July 30, 1888:

It appears that when Prof. Whitney was in Owens Valley himself in 1872 for the purpose at studying the effects of the great earthquake of March 26th of that year, he became unpopular with a good many people in the Valley, some of whom took a very strong personal dislike for him. When, therefore, a year later it was suddenly discovered that a lower mountain had for three years been called Mt Whitney by mistake some of these people thought it could be a fine opportunity for revenge upon the man whom they disliked by making his name stick to the lower peak and calling the highest one something else.

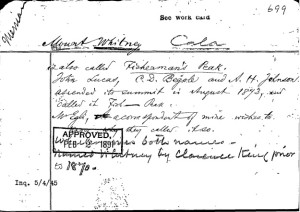

It was not until Feb 2, 1891 that the U.S. Board on Geographic Names stepped in and called the fight, in an apparent technical knock out. The hand written decision card can be found on the Geonames website.

Fisherman’s Peak was then relegated to the status of “variant name,” a sort of purgatory waste bin for losing names, recorded in the GNIS database, but never again to be used on any map or official document.

King’s bungling did manage to get his boss some bonus recognition. Mount Langley, the one he accidentally climbed, has a variety of variant names, including False Mount Whitney, Mount Whitney Number One, and Old Mount Whitney.

Although Mount Whitney may have beaten back Fisherman’s Peak, the winds of change continue to howl through the mountains. On October 1st, 2014, white male McKinley was knocked off his (highest in the entire USA) mount, in favor of the local native name Denali. Could white male Whitney be far behind?

The competition for Denali was as high as the mountain. In addition to Mount McKinley, other now discarded “variant” names include: Bolshoy, Bulshaia Gora, Bulshaya Gora, Bulshoe, Churchill Peaks, Deenaalee, Deenadhee, Deenadheet, Deenalee, Deghilaay Ce’e, Deghilaay Ke’e, Delaykah, Denadhe, Denagadh, Denaze, Dengadh, Dengadhe, Dengadhi, Dengadhiy, Densmore’s Mountain, Densmores Peak, Dghelaay Ce‘e, Dghelaay Ke’e, Dghelay Ka‘a, Dghili Ka‘a, Diinaadhi, Diinaadhii, Diinaadhiit, Diinaalii, Diinaazii, Diineezi, Din-al-ee, Din-az-ee, Doleika, Doleyka, Mount Denali, Mount Doleika, Mount McKinley, North Peak, North, Peak Mount McKinley, South Peak, South Peak Mount McKinley, Tenada, Tenda, Tennaly, To-lah-gah, Traleika, Traleyka.

I was disappointed that Boaty McBoatface did not even make the consideration list.

If local names are to be given preference, then shouldn’t we pay attention to what the California natives called the highest continental peak now known as Whitney? To answer this, Wikipedia quotes from Judge William B. Wallace memoirs:

The Pi Ute [Paiute] Indians called Mt. Whitney “Too-man-i-goo-yah”

Given the extremely high number of people fighting each year for a permit to climb Mount Whitney, the name “Too-man-i-goo-yah” seems “too-good-i-think-yah.” I can only offer it up with a degree of amused skepticism. It reminds me of the public relations disaster when a KTVU anchor read the supposed names of four pilots who crash landed Asiana flight 214 in San Francisco: “Sum Ting Wong,” “Wi Tu Lo,” “Ho Lee Fuk,” and “Bang Ding Ow.”

“Perhaps we do need policies on appropriate names,” mused Ray Cyst Baphuny.

In 1997, The United States Board On Geographic Names released a 56 page document titled the PRINCIPLES, POLICIES, AND PROCEDURES: DOMESTIC GEOGRAPHIC NAMES

It includes ten naming policies.

- POLICY I: NAMES BEING CONSIDERED BY CONGRESS

- POLICY II: NAME CHANGES

- POLICY III: COMMEMORATIVE NAMES

- POLICY IV: WILDERNESS NAMES

- POLICY V: DEROGATORY NAMES

- POLICY VI: USE OF DIACRITICAL MARKS

- POLICY VII: NAME DUPLICATION

- POLICY VII: USE OF VARIANT NAMES

- POLICY IX: LONG NAMES

- POLICY X: NAMES OF NATIVE AMERICAN ORIGIN

I suspect POLICY VIII addresses secret names, such as Area 51, and therefore had to be redacted. To make up for it, however, there are two POLICY VII’s, one of which is titled… wait for it… NAME DUPLICATION?!

Our focus, however, is on how to name a mountain. Our attention, therefore, is logically drawn to POLICY IV: WILDERNESS NAMES, which regrettably states:

Within wilderness areas, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names will not approve proposed names for unnamed features, names in local use but not published on a base series map, or unpublished administrative names used by administering agencies, unless an overriding need exists, such as for purposes of safety, education, or area administration.

Name proposals commemorating persons are discouraged…

Before you get discouraged, remember:

… a person must be deceased at least 5 years before a commemorative proposal will be considered.

In other words, you will have plenty of time to get over the injury of your untimely death, before you have to face the insult of your mountain name rejection.

NOTE: A newer version of Principles, Policies and Procedures was released in 2016.

![800px-Voobie_-_Moon_n_Venus_played_hide-and-seek_(by-sa) By Vinish K Saini from Chandigarh, India (Moon n Venus played hide-and-seek) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://howtowilderness.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/800px-Voobie_-_Moon_n_Venus_played_hide-and-seek_by-sa-300x225.jpg)

![800px-Meteor_Bolide By C m handler (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://howtowilderness.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/800px-Meteor_Bolide-300x199.jpg)