When I come upon a bird I don’t recognize, it flutters in and out of my consciousness with very little impact. I make no emotional connection other than to notice: a bird. However when I come upon an old friend, a bird I recognize and know, the reaction is completely different.

Ah look, a little nut hatch. One of those amazing acrobats who can forage through trees upside down. I remember the time my kids, using sunflower seeds, coaxed one to land on my wife’s back as she slept on a lounge chair.

The same thing happens to me with trees. When I see one I do not know it is nothing more than a big stick with leaves. But when it is one I know I experience a connection.

Oh look, a Jeffery Pine. The one with gentle pine cones that don’t prick you like the Ponderous cones and if you stick your nose right into the bark it smell’s like vanilla. I remember showing my kids how to to that, and they still do it today.

Crazy as it sounds I feel the same way about trails. Most of us walk on them without really ever noticing them. With limited knowledge of the art and science of trail making we miss an opportunity for a connection, not only to the trail, but to the people who poured their sweat into it its creation. I suppose on the one hand our lack of noticing is a validation of good design. If and when we notice, it is usually for the wrong reasons: massive ruts, standing water, washboard surfaces, or collapsed switchbacks.

So what makes a great trail?

Some of it comes down to simple things; things that don’t require new knowledge or insights; things like:

- Is this trail going where I want to go?

- Is the trail through an area I find aesthetically pleasing?

- Is the trail appropriate for my skill level and mode of transportation?

There is also, however, an entire language of trail design and maintenance. Knowing some of these terms can raise our consciousness. You are probably well familiar with some, such as switch back. Used in a sentence: Oh no, not another switch back. But what about other terms like grade reversal, kick, slough or partial bench. They are all a part of the language and science of trail design.

Design science is required to make trails low maintenance. What is it that conspires against a trail? Erosion – from wind, and walking, and critters, and water… but mostly water. Water is the true enemy of the trail.

To know a trail is to know the water. Where does it come from? Where does it go? What can we do to keep it off the trail? Water is like a lazy person, it takes the path of least resistance. The goal of the trail designer is to make sure that path of least resistance is not path of the trail.

Basic Terms

-

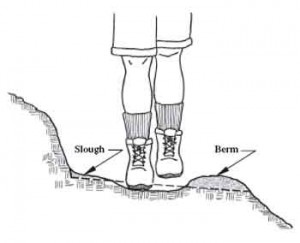

Tread, Slough, Berm: Credit USDT Tread is the part of the trail you travel on.

- Slough is the stuff that collapses down on the tread.

- Berm is the build up on the downhill side of the trail

Trail creep is what occurs when the slough is not removed, encouraging the traveler to walk closer to the down slope. Unless corrected, over time the trail has a tendency to creep down hill. If the berm is not removed and the trail’s proper out-slope maintained, water will be trapped and travel down the trail. A trail that becomes a river will experience significant rutting and erosion.

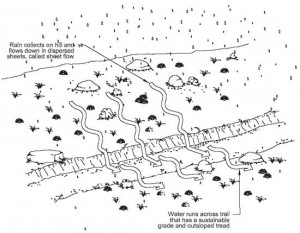

Sheet Flow

When rainfall saturates the ground it travels down the hill in sheets, known as sheet flow. A good trail design, using outward sloping, will encourage the water to quickly flow across the trail in sheets, and not alter its course to join the trail.

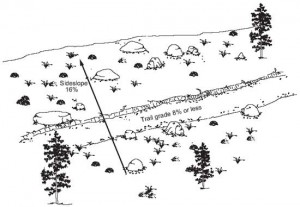

Half Rule:

One technique to encourage sheet flow rather than trail flow is the half rule (made popular by the International Mountain Biking Association). The half rule states that the slope of the trail should be no more than half the side slope. So if a hill is sloping at 16%, a trail crossing the hill should be sloped no more than 8%. When a trail is sloped with a grade similar to the hill, it is known as a fall line trail. Fall line trails are most susceptible to water erosion because they are almost always the path of least resistance, at least for water.

10 Percent Rule

There is a practical limit to the slope of a trail, and most designers will suggest that it should not exceed 10 percent. So even if the half rule allows for more (a side slope of 30% would allow an trail slope of 15%) it’s probably not a good idea.

Grade Reversals

Another technique for keeping water off a trail is a grade reversal. A grade reversal is a temporary reversing of the trail slope. On a downhill trail there is a short uphill portion, before continuing down. If you are coming the other way on the trail, the opposite is experienced; on an uphill trail there is a short down hill section, before continuing uphill. Designed well, a grade reversal will seem completely natural, nothing more than matching the rolling contour of the surroundings. Rest assured, however, that trail designers take particular care in looking for and creating opportunities for these rolling grade reversals. Not only are they aesthetically pleasing, they force the water, which only travels down hill, off the trail during these anti-gravity portions.

Water Bar

Oh so long ago, when I was a young scout, we occasionally did trail maintenance work. At that time one of the key techniques for moving water off a trail was a water bar. The idea was to create an obstacle on the trail which diverted the water off. The obstacle might be a log, a row of rocks, or even a built up berm of dirt. The problem with most water bars is that they are not built at the correct angle. When water rushing down a trail hits a bar causing a sharp redirection, it often deposits the sediment it is carrying. This sediment builds up and eventually spoils the bar, allowing future water to overflow it. It turns out that in most cases a water bar is not a very good low maintenance solution. Thinking back on all the probably completely incorrect water bars I helped create, I could just, well, kick myself.

Kick

Standing water is also a significant problem on a trail. Not only does it create the potential for a muddy bog, it also encourages traffic to step around the mess, widening the trail and the size of the mess. It is actually better for a trail if you walk right through a puddle rather than around, but not many do.

A kick is a technique to create a slopped exit for the water from a puddle prone area. Well designed, it is a subtle large dug out semi-circle, with significant enough drainage slope for the water, but not so significant it trips the traveler.

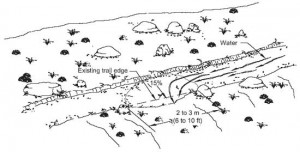

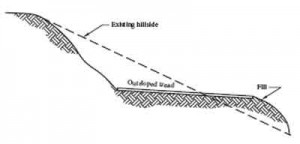

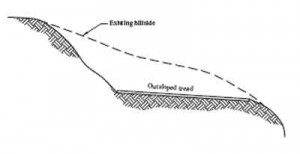

Tread Bench

When a trail is cut into a slope, it can be with a full or partial bench. If the tail is built with a combination of removing dirt from the uphill side, and re-using that dirt to build up the downhill side, the results is a partial bench trail. In theory it takes less work to create, but results in a less stable and sustainable tread.

In the full bench tread the dirt is removed until the trail has the appropriate out-slope, and does not require artificially building up the downhill side. More digging and removing of dirt is required, but the end result is a much more stable and sustainable tread. Most trails created now use a full bench approach.

Rock Armour

In areas where the ground is particularly susceptible to erosion, rocks may be used as reinforcement. Examples include creek crossings, switchbacks, or trails on extremely steep side slopes. A tremendous amount of manual labor goes into these stone jigsaw puzzles. If only as an excuse to rest, occasionally stop to admire this amazing work.

Social Trails

Travelers do not always stay on the trail. Some land managers see these creative travelers as the problem, some travelers see the trail designer as the problem. When a trail meets the needs and expectations of the travelers, they tend to trod on the tread. However, a poorly designed trail will encourage travelers to find their own path. This may be a perceived minor improvement, a short cut or slight re-routing. Or it may be the creation of a entirely new trail. These user created trails and routes are often called social trails.

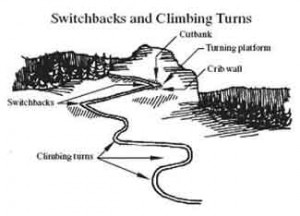

Well designed trails subtly prevent this socialization. If travelers can see far ahead, and the trail seems the most logical route, they will stay the trail. If they can see a better way, a shorter or easier path, they will be tempted to alter the course. Switch backs are common areas where a short cut is tempting. By limiting sight lines to the trail ahead, and by intentionally routing switch backs around obstacles, such as rock outcrops and trees, the short cut becomes less alluring.

Trail Maintenance

Even a well designed trail requires maintenance. Crews of workers, paid and volunteer, are required. With a raised consciousness of trail maintenance you can help by spotting and correcting minor problem in the field. Or at a minimum, you should know enough not make them worse.

Great source of trail design and maintenance information:

U. S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration: Trail Construction and Maintenance Notebook