Let me start by saying that I am neither a caveman nor an expert in paleolithic food consumption. I have not published a PhD dissertation comparing The China Study with benefits of dino-dining. I leave dietary science research to the more qualified, or at least the more openly opinionated. I’m just a simple minded outdoorsman, trying to make my way through the wilderness carrying as many calories in as few grams as possible.

Let me start by saying that I am neither a caveman nor an expert in paleolithic food consumption. I have not published a PhD dissertation comparing The China Study with benefits of dino-dining. I leave dietary science research to the more qualified, or at least the more openly opinionated. I’m just a simple minded outdoorsman, trying to make my way through the wilderness carrying as many calories in as few grams as possible.

What is the Paleo Diet?

Perhaps oversimplifying, the Paleo Diet consists of foods that were available and consumed during the paleolithic period. In the unlikely event you’ve forgotten, paleolithic refers to the Stone Age, starting 2.5 million years ago and ending 20,000 years ago. The Paleo Diet is generally described as the diet of the hunter-gatherer. In other words, Paleos had to either kill it or find it on the ground. I am guessing the 3 second rule was longer then, maybe more like 3 weeks. At any rate, the diet was made up primarily of meat, vegetables, and seasonal fruit. Products of the future agriculture age, involving food processing and probably government labeling, were not included. Grains, pastas, and breads are not considered part of the diet. So in other words, hamburger yes, hamburger helper no.

Perhaps oversimplifying, the Paleo Diet consists of foods that were available and consumed during the paleolithic period. In the unlikely event you’ve forgotten, paleolithic refers to the Stone Age, starting 2.5 million years ago and ending 20,000 years ago. The Paleo Diet is generally described as the diet of the hunter-gatherer. In other words, Paleos had to either kill it or find it on the ground. I am guessing the 3 second rule was longer then, maybe more like 3 weeks. At any rate, the diet was made up primarily of meat, vegetables, and seasonal fruit. Products of the future agriculture age, involving food processing and probably government labeling, were not included. Grains, pastas, and breads are not considered part of the diet. So in other words, hamburger yes, hamburger helper no.

I have no idea how we know exactly what these homo sapiens did and did not eat. Perhaps anthropologists have examined cave drawing banner ads, or conducted internet polls. These experts seem pretty confident that forbidden items include: refined sugar, grain, dairy and legumes. Some actually say the only vegetables Paleos can eat are ones that do not require cooking. It is okay to cook and eat vegetables not requiring cooking, just not to cook and eat the ones requiring cooking. My stone age cerebral cortex is throbbing.

As a side note, I have found no reference to cannibalism. I assume if it occurred during the paleolithic period it would still be okay today, but cannibal helper would be strictly forbidden. Assuming of course I got all this right.

Paleo Backpacking

As I consider them, the similarities between Paleo-sapiens and Backpack-sapiens are indeed eerie. Both are clearly:

- mobile wanderers

- opportunist gatherers

- occasional hunters

- fire makers

They are also

- usually hungry

- dirty and stinky

Paleo-Packer Compatibility

Many of the traditional backpacking staples are clearly non-Paleo. The modern Paleo-Packer would have to brutally club to death his desire for oatmeal, ramen, and even the peanuts (legumes) from good old raisins and peanuts (GORP). Many of the things we consider non-perishable and light weight are disallowed, where as things that are perishable and heavy, such as fresh meat, vegetables, and fruit are just fine.

Surprisingly, almost every Paleo recipe book includes sweet potatoes. Apparently the paleolithic landscape was simply littered with wild yammers. I am not sure how wild; for example, were they gathered or actually hunted? At any rate, they must not have required cooking, but they probably were, since all of today’s recipes call for it.

Surprisingly, almost every Paleo recipe book includes sweet potatoes. Apparently the paleolithic landscape was simply littered with wild yammers. I am not sure how wild; for example, were they gathered or actually hunted? At any rate, they must not have required cooking, but they probably were, since all of today’s recipes call for it.

Another popular modern Paleo dish is called Pemmican. Pemmican is a supposedly nutritious concoction of fat and protein. Used as a high energy source by arctic explorers, it can be made from whatever resources are available: beef, bison, deer, elk or moose. Pemmican is basically 50% dried pulverized meat, combined with 50% clarified (melted) animal fat. In some cases berries, such as chokeberries, are added. Seriously? How much choking can one energy concoction contain?

Paleo Backpacking Options

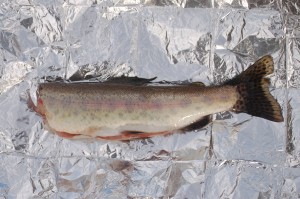

As I hunted through various resources, websites and books, I was able to gather a list of traditional or at least common Paleo Backpacking food choices:

- Pemmican (though it may melt in warm climates)

- Foil packed tuna

- Foil packed chicken

- Jerky (beef, turkey, elk)

- Summer sausage

- Salami

- Sardines

- Almond butter

- Dried fruits (apples, apricots, bananas, mangoes, dates, etc)

- Raw or dehydrated vegetables (sweet potatoes, yams, broccoli, onions, peppers, mushrooms, zucchini, etc)

- Coconut Oil

- Almond flour products (muffins, pancakes, whatever)

Unsolicited Advice

Through my research I also gathered there is a non-believing splinter clan whose advice can be summed up as:

Hey caveman, shouldn’t you be spearing and clubbing your way through the wilderness?

The problem here of course is the word advice. According to the North Carolina Board of Dietetics / Nutrition, offering advice on Paelo diets without a license is illegal. They have aggressively gone after Steve Cooksey, clubbing him over his Paelo diet blog. The Institute for Justice has joined the fray, offering their hairy-knuckled support for the Paleo blogger. They are now representing Steve in a free speech lawsuit against the North Carolina nutrition board (Cooksey v. Futrell). You just cannot make this stuff up.

It is ironic that a caveman has launched a free speech lawsuit against a modern science board, whose intellectual beef against him appears to be “ugh“. That of course is merely my opinion, and not advice. In fact, nothing in this Paleo diet article should be construed to be advice. Personally, I would advise against anyone offering advice, if doing so were not clearly illegal, at least according to the North Carolina Board of Neanderthals.

I do wish the caveman Steve well in his lawsuit, and hope the North Carolina board ends up consuming a significant portion of humble pie. Is it okay if I recommend the Paleo sweet potato pie? Probably not.